Grief & Loss

Between 2009 and 2017, I lost my mom, my dad, my brother, and my dog. This is writing done in direct response to those losses, or related in some way.

The Rain Came

Well, the rain came. Misty floating pillows of it, directionless and soft. Unthreatening, it promised not to interfere with anyone's plans. Then I guess it changed its mind, or just got tired of holding its own weight, and the tin roof above me became a drum. In the pitch black bedroom I pulled up the covers and listened. Each drop was a glass marble surrendered by a sky too full to keep them. Hundreds of marbles fell, then thousands, until the wind stepped in and picked up a slingshot, and the marbles hit with such ferocity I expected to see moonlight piercing through at any moment.

The rain loosened the soil on the cliff above the house, shaking down small stones and clumps of earth. I had the sensation of being buried alive, and with each crumbling patter I pictured faceless mourners tossing handfuls of dirt onto a casket.

It woke me up periodically, from feverish dreams that either made no sense or too much of it, I'm not sure which. One saw Terence embracing me lightly from behind, turning my cheek to kiss me with an adroitness I hadn't remembered ever knowing. He evaporated, leaving me melting and unsure, and standing at the edge of a shallow pond. Someone dared me to wade to the center of it. And when I did, I found a circle of my friends scowling at me in disappointment. I didn't know what I'd done; I only knew I'd confirmed their worst suspicions.

We had a sort of Thanksgiving. The family, myself, and three neighbors whom I tried terribly hard to impress. They must wonder who the hell I am, I thought uncharitably of myself - of them. What gives with this stranger, this interloper from across the country? She is not blood. Where is her own family?

Woody, of course, knows the answers to those questions now, and probably wouldn't ever have asked them anyway. He and his wife (tennis buff, no nonsense but quick to laugh) brought spaghetti squash, sea-salt dark chocolate caramels, a pumpkin pie the size of a manhole cover, and a bottle of Sauternes. The Sauternes really deserves its own post, honey bright and smooth and lip-licking sweet. It was my first, which made it special to me. And it was the first Sauternes Bill has had in decades, which made it special to him. He and Hannah used to order it as a young couple in California - I believe he said on trips to Mendocino. His face when he spoke of it - laughing about how little he knew of wines back then - briefly lost all of those decades. Woody, too, had a Sauternes story to tell. A group of nine friends, gambling one day on a $900 bottle they had to split, well, nine ways. $100 per man, for about a sip. Worth every penny.

Today the rain abandoned all restraint, laughing at me, spitting in my face as I stubbornly rounded up the last day's worth of photos. The wind turned Hannah's umbrella into a sail, and I nearly toppled into the water trying to take a selfie at the end of the dock.

I didn't have a great day today. Sleep has evaded me all week for a combination of reasons, twisting my nerves into a bundle that threatened to snap at the slightest provocation. And provocation came tonight, in the form of a nasty burn running the length of my forearm. I was making vegetable chowder (Hannah liked it so much the last time I made it) and I stupidly used a short-handled cup to ladle some of it into the blender. My elbow grazed the lip of the pot and I jumped, splashing piping hot soup onto myself, my favorite navy cashmere sweater, and the floor.

Everyone swarmed to help me. To clean up my mess, to treat my burn, to fetch me painkillers. Their solicitousness sent me sailing over the edge, and I had to brush tears - humiliating, childish tears - from my cheeks so I could see to finish my cooking. At the table the meal was subdued, heavy with the tone I'd set with my overreaction, and it wasn't long before Bill's gentle prying unleashed the truth underneath the ostensible reason for my tears. I was exhausted, anxious about returning home, lonely for friends who wouldn't be there when I got back, and generally in a storm of self-doubt.

Not exactly the note I wanted to leave on. I mean, I didn't say all that, though the subject of my breakup did come up momentarily. But they could see I was fraught with worry and sleeplessness, and Bill ordered me to bed early.

That was seven hours ago; only one of which I slept for.

Oh god, here it comes again. I wish you could hear it. Great gusting sheets, surging suddenly just now as if desperate to drown out my bleating self-pity. Or maybe gently wash it away. Maybe the rain is a friend tonight.

Anyway, friend or foe, it turned the lake and its surroundings into a crayon box today. It wicked the leaves down from trees that weren't ready to release them; they were still too bright, too alive. They lay stunned on the ground - a wet, waxy palette of goldenrod and ochre, strawberry and chartreuse. I feel guilty filtering pictures of them, like I'm adding salt to food that's already plenty seasoned. So only the tiniest bit, to make sure their vibrancy comes through loud and clear.

The sound of the rain, though - that you'll have to imagine. And now, for me, sleep - though maybe I'll have to imagine that.

The Clouds Themselves

The 24-hour Korean spa that I visit a few days after my dog dies--my eyes puffy from lack of sleep, my shoulders sore from body-racking sobs--requires nudity.

I know this going in. I've read the reviews, I understand the etiquette. Still, it takes a few laps around the labyrinthian locker room to work up enough nerve to shed the uniform issued to me upon check-in: mustard yellow t-shirt, baggy khaki shorts, brown rubber flip flops so thin my ankle bones crackle on the hardwood floor. I'm pretty sure the ensemble is purposefully designed to be as ugly as possible, so patrons will want to leave sooner.

A wall of paneled glass, closed off with curtains except for double doors on which are etched the rules, leads into the main spa area. Jacuzzi. Cold-water dipping pool. Sauna and steam room. These facilities are bookended by a series of standard showers on one side, and on the other, three rows of some other kind of bathing stalls that I don't quite understand. Short, tiled booths with detachable shower hoses and plastic stools for sitting. Something ritualistic and exotic about them intimidates me, makes me feel like a prudish outsider. As I walk past these washing stations with averted eyes, I expect to catch glimpses of grey hair, loose skin. Instead they are occupied by lithe young bodies and heads full of sleek black hair.

It's 1:00 am on a Saturday morning, and there are easily three or four dozen other women here. We're all naked. We're not all Korean.

He isn't with me here. There's no reason he ever would be in a place like this, so it's easier to forget him for a few minutes. Heartbreak doesn't exactly leave, but it abates, lessens to a dull throb. I press my shoulders hard against the dry wooden beams of the sauna. Sink my fingers as deeply as I can into warmed-up muscles. Breathe in, then out. Life goes on. You've been here before. There's no holding onto anything, or anyone.

A heavily-accented woman's voice pierces my thoughts and I realize I'm being summoned. The numbers she's calling out match the ones on the plastic, waterproof bracelet around my wrist. The bracelet serves as identification, and also syncs with the locker I've been assigned.

"Seven forty-tooo? Seven forty-tooooo?"

I emerge from the sauna with my hand raised, feeling sheepish and extraordinarily exposed. "Here! I'm here." Glances shoot my way which feel disdainful, though I'm probably imagining that.

The woman who leads me to the separate area where services such as massages, facials, and other treatments are administered is not naked. She is in fact wearing lingerie, or some approximation of it. Tiny black tap pants. A lacy black triangle bra. She's sixty if she's a day.

With a few impatient gestures I am directed to lay facedown on a vinyl massage table sheathed in clear plastic. My skin, hot from the sauna, sticks awkwardly to the plastic as I try to shift into a more comfortable, more dignified position. But I'll understand soon enough the reason for this prophylactic measure: the entire treatment area is tiled, with drains underneath each low-walled cubicle. When things get messy (which they will; I've opted for an oil-based massage), guests can simply be hosed off like elephants at the zoo. After a massage the acrobatics and detached intimacy of which confirm all my presuppositions, bucketfuls of warm water are dumped over me, washing away the oil, and with it the last of my worries. Or such is the idea. Alas.

Alas.

I don't linger long after the massage. One more quick round of the sauna and steam room, then I walk to the wall where I've stashed my t-shirt and shorts in a plastic bin At this point I'm no longer fazed by my own nudity. I don't face the wall as I dress. The place seems to have cleared out anyway. It's time to go home. There is no more putting it off. I remind myself that it will hurt a tiny little bit less every day, until it becomes bearable. But already my throat is thickening and my fingertips tingling. I think of his face and the pain makes me gasp.

Outfitted once more in my own clothes, I trudge up the stairs to turn in my wristband and check out. The cold night air is bracing and black and joyless. I have a twenty minute walk ahead of me. My hair is wet and tangled, but I don't much care.

As I round the side of the building, I hear male voices and laughter issue from somewhere along the curbside, where every inch of precious Koreatown parking has been utilized. It's dark though, so I don't see the source until I'm directly next to it: two men sitting in the front seat of a beat-up mid-90s Nissan, the windows rolled down and passenger-side door swung wide open. The engine is off, as are the car's lights. I'm almost past the vehicle when one of them calls out.

"Hey, how's it going? How was the spa?"

Out of surprise more than friendliness, I stop, bending over to better see the strangers while still maintaining my distance. The faces that peer back at me are grinning and guileless. Both thirty-ish. One fair, one dark. Casually dressed. Well-groomed. Neither particularly bad-looking.

"Great," I reply. "First time. Place is a trip."

"Isn't it, though? Did you check out the rooftop?"

"No. I didn't even realize there was one."

"Oh yeah, and it's awesome. Co-ed floor is crazy, too."

"Co-ed floor? I didn't even know about the co-ed floor." Hearing this news, I feel I've failed somehow.

"Yeah, but you have to wear the uniform."

"Ah, okay," I say, as if consoled. I'm about to dismiss myself and press on when the two introduce themselves. Brian and Zack. We wave polite hellos in the moonlight.

"You seem nice. Do you want to smoke a joint with us, before we go in?"

There is no reason to say yes to this absurd invitation. Two strange men sitting in a beat-up car, in the middle of the night, on the fringes of Macarthur Park - a place I don't want to be even in daylight. But the thought of the alternative - that is, returning home and facing a fresh round of the shattering grief that awaits me there - eclipses my better judgment. And anyway, nothing about these guys reads predatory. My gut says go for it.

And so with a shrug at how fucking weird and wonderful the universe can be, I accept.

The three of us walk around to the front of the building, ambling and talking for another half block until we reach some stone benches underneath a tree. We're on Wilshire Boulevard, a busy thoroughfare. There's still a decent amount of traffic, even at this hour. I'm not concerned, though. I'm too busy trying to wrap my brain around the information I've just received: Brian and Zack are youth pastors.

At first I don't believe them. I accuse them of trolling me. But the pair is sincere. They've got stories. They've been doing it a long time. They've been friends a long time, too. They're aware of how odd a light their current behavior casts them in, and try to explain themselves more. I probe, genuinely fascinated. The more I learn, the more I suspect that neither is a true believer. It seems to be something they fell into by way of a charismatic church leader. The word "cult" floats through my brain, but I stay diplomatically silent. They've got weed, after all.

I'm not a pot smoker. It's just not my drug. It makes me dopey and slow and paranoid, and doesn't work well with my body chemistry. Leaves me feeling blah.

But blah is better than broken, so I take all three hits that are offered to me before thanking my benefactors profusely, and saying goodnight.

Okay. Well.

The walk home is both interminable and fleeting. Once there I cast about for something to put my attention on. Can't read. Can't write. Want to talk to someone, but it's 2 am. There's always a chance my best friend awake; he keeps crazy hours. I re-read our last few exchanges. Zero in on the message I sent a few hours after night it happened. Thursday, February 9th, at 3:02 am, when I found out that the news had been shared. My boyfriend had thoughtfully told my best friend, so I wouldn't have to say the words myself.

I'm sorry. I didn't know he was going to tell you.

Anyway.

It was bloat. The surgery would have been $6-8k. And he was 10. And I hadn't told you but he slipped really bad about a week ago and had been limping way worse than ever.

I'm sorry you found out this way.

He loved you so much.

I don't know what else to say right now.

It's never been so quiet.

---

The night my dog died, the streets of Los Angeles were thick with fog.

LA is never foggy. The coast, sure. But never the city. In fact I'd never seen anything like it. I noticed it when I got off work: hazy streetlights and a slickness in the air. By the time Timo came over to hang out, you couldn't see twenty yards in front of you. Everything was shrouded, romantic and dramatic and mysterious. Sounds disappeared in the night.

Maybe Chaucer felt the strangeness. Maybe it tickled his senses, delighting him into being especially playful. Trotting more quickly down the dark alley beside my building, his passageway out for a walk. I don't know. Timo doesn't know, either. Both of us took him out that night, in pretty quick succession, because he hadn't gone potty after we fed him. Perhaps he was more keyed up, thanks to the weird weather, or because Timo was there.

He adored Timo.

There is no knowing exactly how or when it happened. If he jumped, or if he drank water too quickly. But it became clear pretty quickly that something was wrong. Retching. Heaving. He wouldn't settle. Wouldn't lay down. My increasing nervousness turning to panic, turning to dread in the backseat of the Uber we called when the 24-hour emergency vet said to bring him immediately.

I knew, of course. Not that it was bloat specifically but that something was very, very wrong. I just knew. And I held my sweet pup in the back of that car and stroked his shaking body, and just let silent tears pour down my face. And Timo reached back and squeezed my knee and I felt nothing, because the most beautiful part of me was dying, and I knew it.

---

It was foggy the night my best friend left the world.

Fog that wrapped itself around our car as we sped down the freeway, hiding everything from me except his perfect, sweet face. Fog that hugged the animal hospital like soft cotton, muffling cries that tore through me like fire. Fog that gently closed us in, just the two of us, him breathing heavy with sedation, strapped in a tragicomic display of last-moment silliness to a gurney, looking like some kind of spa guest in his white towel, in the room they gave us for our goodbye.

Of course it would be that way. The fog. Because how else would he get into dog heaven?

The clouds themselves had to come down to carry him up.

One Less Bottle

It was surprisingly easy to go through my dad's things, after he died. Occasionally, I'd stumble into a moment of paralyzing nostalgia. Some ostensibly harmless personal effect of his - a handkerchief, a slide rule, a Zippo lighter - would reach my hands and burn as if on fire. Just some thing, with the power to trip up my pragmatism, to laugh at it. This is so him, I'd think. Emblematic. Representative. I'd recall its place in my father's life, delicately fingering every facet of the memory. And the breath would be knocked out of me for a few minutes while I let grief wash just over me, unchallenged.

But for the most part, I maintained an attitude of stoic resolve. All this shit has to go.

You can't keep everything, after all.

The liquor posed a problem. Not the stuff that was still sealed - Greg and I didn't have to think twice about what to do with that. We packaged it up and shipped it back home to LA (though sadly, it never made it here). But there were several bottles of entirely decent (even decent plus) alcohol that, as established and accomplished lushes, Greg and I were loathe to drain down the sink.

So we started giving it away.

One afternoon, the cable technician came to collect some equipment. He was somewhere solidly in his sixties, a man whose stooped demeanor and perceptible limp belied an otherwise rugged vitality, and an earnest face. He'd probably seemed sixty-something for the past twenty years, and would probably continue to for another twenty.

As he was putting together some paperwork for me to sign, Greg ambushed him in the friendly way he does. "Sir," he said, "I don't suppose you're a whisky drinker?" He assured Greg that he was, in fact, precisely such a man. And before the technician could say "nonrefundable deposit", his erstwhile customer's daughter's boyfriend was presenting him with a two-third's full bottle of Dewars.

The man accepted the gift with grace. He must have been putting two and two together already, what with the boxes, the general disarray of the house, and the cancellation order he was there to fill. Greg probably confirmed his suspicion when he told the man that the liquor's previous owner would appreciate passing on the bottle to a worthy and appreciative trustee. The man looked at me. He said some kind words. I wish I remember them exactly. Or maybe it's better I don't.

A look came across Greg’s face, and he stepped out of the room with some unknown purpose. He returned a moment later, a roll of blue painter's tape in hand along with a black Sharpie. He tore off a small piece of tape and carefully stretched it across the bottle of Scotch. He spoke as he wrote on it. "The only requirement is that when you pour yourself a glass tonight at home after work, you have to raise a toast and say this." He smiled and looked up from his handiwork to me. I read what he'd written. To Norm. I swallowed and smiled back.

More warm words from the technician. "Wonderful young woman", "good souls" - something like that. Small dabs of salve on a freshly blistered heart. We walked him down the driveway to his truck. He asked my name and shook my hand. Then he had an idea. "I'll tell you what," he said. "I'll do you one better than just a toast. If you give me your phone number, tonight when I'm ready for my drink, I'll call you guys up, and all three of us can drink to your father at the same time."

I looked at the man. I looked at my boyfriend. I felt, straining its way through the clotted, hard dirt of loss, a tiny shoot of joy. How had they done that, these two men from different worlds, with nothing in common but big hearts and a gift for awing me with their thoughtfulness? They made it look so easy.

He called us promptly at the appointed time. Greg took the call, and put him on speakerphone. He had the man hold while we scrambled to pour our own drinks. All we had on hand was vodka and apple juice. It was perfect. We lifted our glasses and told the stranger on the other end of the line that we were ready. And that's when my heart, already squeezed to near suffocation by this moment, was clenched just a bit more: the man said, "What sort of man was Norm? Tell me about your father."

I made a sound, something like "Ohhh," a mixed exclamation of surprise and laughter and I don't know what else. Oh, wow, I wasn't expecting that and Oh, wow, if you only knew just what a character he was. "He was an engineer," I began, carefully. "He loved to read. He...taught me to question everything." I was grasping, falling. Greg saw it, and chimed in cheerfully. "He was a ladies man, too." We all laughed, and something came loose inside of me. Some knot of sadness, born of the fact that there was next to no one around to mourn my father's death. Next to no family, next to no friends. It had broken my heart on his behalf. But here, now, an utter stranger was honoring my dad in the purest way possible: truly caring about who he was. Making him matter, if only for a moment.

After our clinks and drinks, the man again offered his sincere condolences. He praised me as a daughter, from the little daughtering he'd witnessed that day. He invited us, should we ever find ourselves back in his small town again, to dine with he and his wife. I thought wistfully of that dinner, which I knew would be lovely and probably somewhat life-affirming, but which I knew would never happen.

We said our goodbyes, rinsed out our glasses, and continued sorting late into the night. We had one bottle less to pack.

Black Outlines

There are two sides to my father's death. There are the plain, cold facts of what happened, and there are all the little details that fill in those black outlines with color. I need to get them both out of my head. Here are the plain, cold facts.

My first few weeks in Florida were overwhelming to a point of comedy.

My dad had no one but me to take care of him. His brothers and he had long since ceased speaking. There was a cousin, herself elderly, unstable, and unavailable. That was it, as far as his family of origin. As far as his own family? His ex-wife was dead, and his son was MIA. He had no close friends, and certainly none close by enough to help.

So I was it. And I was in way, way over my head.

I can't claim to have hit the ground running when I got there. More the opposite: I faltered and flailed about for the first few days, terrified and in denial of the situation. Feeling sorrier for myself than him, really. But once it became clear that my father was becoming more helpless by the minute, some survival mechanism in me clicked into gear. I made calls, set appointments, did research, and shuttled him to doctors. I wrote lists, asked questions, picked up supplies and medicines. I created three different schedules for pill-taking, in an effort to make it easier for my father to keep track of the seven prescriptions he was taking (none worked). I cooked and cleaned and counseled my father as best I could. When he started to lose mobility, I rearranged furniture, and even sold some things just to get them out of the way. I acted as liaison between him and the panoply of specialists he'd collected in a few short days since his diagnosis.

And speaking of his diagnosis. Here's that, in a nutshell. On April 7, my 73 year-old father was admitted to the hospital with pneumonia. They didn't like what they saw, so they kept him overnight, and ran tests. A day and a half later, he was informed that he had small cell lung cancer. I was on a plane two days after that. Four days after that, his radiation oncologist gave him a prognosis of 6-12 months. But the doctors were optimistic about treatment, affirming that my dad would be healthy enough to undergo several weeks of chemotherapy and radiation. They even said he should be able to drive himself to his appointments.

Hearing that, I was utterly nonplussed. It seemed obvious to me that he wouldn't be able to care for himself on a basic level (eating, bathing, etc), much less have the strength to take himself to treatments. But maybe they were right? Maybe the bad state he was in was temporary, and he'd rally? Maybe I could manage his care from across the country at first, coming out every few weeks and stepping up my presence as necessary, as things devolved? I conferred with one of his doctors. And by "confer" I mean, I practically clutched the man's coat lapels, voice shaking, and asked, "What the hell do I do?" He told me my "plan" was a good one, and that'd I'd know when my dad would need more help. I'd know when things were getting worse.

He was right about that. Things got worse, fast, and I knew it. I saw it with my own eyes. Those first few nights, when we were making early rounds to specialists to get a plan of care in place, were hell itself. He had completely lost his appetite, and dropped 20+ pounds in a matter of a couple weeks. He was consequently too weak to move much, but so mentally agitated that moving around was all he wanted to do. The cancer had spread from his lungs to his ribs and spine, and he was incredibly uncomfortable, even with the morphine. He was depressed and afraid. He'd sit in his office chair for five minutes before insisting on moving to the living room sofa, which after another five minutes, he'd want to get up from, and go lay on the bed. He didn't want to wear pants, and I couldn't get him to stand in the shower long enough to wash off. Incontinence kicked in. We (meaning me) were still tweaking his morphine dosage, trying to find a happy(?) medium between lucidity/pain and bombing him into a speechless semi-coma.

It broke my heart to watch my father, always the vainest man I'd known, forced to abandon his dignity in such a manner. As for me, I had no clue what I was going to do. I had no idea what I was facing, or how long my father was going to be like this. It was clear as day I couldn't leave him and go back to California. Did that mean I had to move out here for the next half year, year, to be his sole caregiver? Would I even be able to do that?? What the hell did I know about caring for a sick person, much less one who was dying? Visions of me trying to bathe him, taking care of his bathroom and hygiene, spoon feeding him and checking his IV, managing all those medications several times a day, etc. wracked me. What. The. Fuck.

I was bewildered and lost. When the occasional nurse or insurance person or hospice worker that I spoke to found out I was handling everything completely on my own, the compassion and solicitousness with which they responded broke me every time. I'd chin up and thank them politely for their concern, but inside, the little girl in me was throwing pity party confetti in the air: Yes! I know! It IS incredibly unfair, right? How am I supposed to do this?? After a while, I stopped pretending to be strong and just let them throw their arms around me for a virtual hug.

The kindness of strangers saved me in those days - the acknowledgment and validation that no one should have do what I was doing, alone.

And so the second week went, with him leaning on me more and more every day, literally and otherwise. He didn't want to eat, so every few hours, I'd spend several minutes trying to coax him into a few bites of ice cream, or chocolate milk - anything dense in calories, in an effort to keep some meat on his bones. He was completely at a loss re: tracking his medications, which needed to be taken every two hours. I couldn't trust him to remember, so I gave up on my fancy charts and checklists and just set my own alarm. He became disoriented and confused about place and time. I awoke on Saturday at three am to him calling me frantically from across the house. I found him fully dressed, sitting near the front door, convinced that he was about to be late for an appointment. When I explained that no, he had no commitments that day, he became inexplicably angry and threatened to hit me.

I'd take advantage of his moments of lucidity to talk to him. We even managed, in the first few days, to have a couple of restaurant meals. I sat across from my father and we looked at one another, the dead weight of his prognosis making each forkful feel like a thousand pounds of sand to swallow. We did our best, though, with small jokes and the occasional sincerely loving exchange. I told him in no uncertain terms what he meant to me, and how I credit all my favorite parts of my personality to him. He told me that despite what I'd convinced myself of, he was incredibly proud of me, of who I'd turned out to be.

Back at home, the restlessness was a killer. He just refused to stay still for more than a few minutes at a time. But with every hour, he lost more and more strength and balance. Each time he wanted to move, I had to be there, lest he go crashing to the ground. At first, the support of my shoulder was enough. Then, he'd need me to walk backwards in front of him, so he could hold my outstretched arms. By the time I went to buy him a walker, he was so frail from lack of food that falling was a near-constant concern.

And then he did fall.

At 2am.

And I couldn't get him back up. And he couldn't get himself back up.

Just that morning, he'd been enrolled in in-home hospice. We'd been at the oncologist's, and I had pulled him aside, wild-eyed with lack of sleep, and said, basically, "Look. If you think he's strong enough to undergo several hours a week of chemo, you're out of your mind. And aside from the issue of chemo, I need help. Badly." The doctor agreed that it was time for hospice, even though he still felt confident that my dad could do chemo. We went home and I spent the afternoon learning just how much support I was about to get - I knew nothing whatsoever about hospice. As it became clear that I would have a team of professionals acting as reinforcements, I slowly let more oxygen into my lungs. I can do this, if I have help. Help is coming.

Help came that very afternoon. He was enrolled, the paperwork was signed, and all the ugly but necessary documents placed on file (his living will, his DNR order, his funerary wishes, etc). A hospital bed was set up in the living room, because my father refused to give up the ghost on the waterbed in his bedroom. He was still adamantly insisting, even in his degenerative state, on climbing in and out of it all day and night.

That's what he was doing, when he fell. Trying to get out of the goddamned waterbed. And I was helping, but not well enough, obviously. Because suddenly he was on the ground, moaning in pain, and I couldn't do a fucking thing about it other than try to dial down my hysteria.

That was one of the hardest, most awful moments of the whole ordeal. But it was by no means the worst. No, cancer is an endless swag bag of heartbreaking surprises!

Anyway, I called hospice, who sent help as quickly as possible. It took almost an hour. During that time, I ostensibly sat with my father, covered him in a blanket, held his hand, propped his head, and talked to him (he didn't talk back). But what I was really doing was facing the fact of my father's impending death, and taking the first wretched step towards accepting it.

The EMTs arrived, and lifted him into bed. I got more What, wait? It's only you here, taking care of him? type pity. I ate it up, greedily. His hospice team's head nurse, upon learning of this incident, upgraded him to continuous care - I was told as much over the phone. By 8am, a certified nurse would be there to help, and, I was told, there'd be someone staying with us, at the house, 24-7 from that point on.

America's Favorite

My mother snuck up on me tonight. She likes to do that, when I make a cup of tea.

Tea was her clock and her comfort. She fixed a cup first thing in the morning, rawboned and pensive in faded flannel pajamas. Thinness kept her girlishly limber into her fifties, and she would sit with her knees drawn tight to her chest like a child at story hour, a faraway look masking her thoughts as she sipped. In those moments it was as if her whole body were wrapped around the mug, pulling heat and strength and reassurance from its steam.

All day. She drank it all day. With meals and afterward. Between chores and before bed. My mother drank tea the way some people smoke tobacco: agreeably and pleasurably chained to it.

She drank cheap American tea, which she prepared the tragically American way: by nuking a single-serve baggie in cold tap water on high for two and a half minutes. As I child I thought microwave ovens worked by conventionally heating their contents, only with greater power. When I learned they actually operate through radiation, I was terrified to think what my mother was ingesting from those little bloated brown bags of leaves. Now I know whatever poisons irradiated Lipton left in her blood were nothing compared to what the alcohol did. But kids aren't always good at recognizing the enemy.

Tonight I wanted to wrench more from the dwindling evening than my brain seemed prepared to give, and past a certain hour coffee just feels obscene - so I made a cup of tea. The cabinet is stocked with Earl Grey, peppermint, and chamomile, not to mention a half-dozen tins of Terence's oolongs and greens and other more exotic blends. But I chose from the bright yellow box with the red and white logo - the one containing several dozen miniature envelopes packed in cheerful uniformity. The cheap stuff. America's Favorite Tea. Well, perhaps. One American's that I can attest to anyway.

I can't drown it without smelling it first. And that smell is everything. Things I've known and things I'll never understand. Things familiar and things forgotten. Things that make sense and things that have no business speaking to me at all, much less from the depths of a delicate paper packet the size of a pocket watch. Orange blossom, pepper, and miscommunication. Timothy hay, chocolate, and blame. That smell is my mother.

A funny thing about tea, though: its scent seems to fade under the kettle's boiling spout. So she comes sometimes, when I reach into the bright yellow box. But she rarely stays longer than two and a half minutes.

My Father's Yard

Wild things grow in my father's yard.

Things lush in texture, riotous in color. Things unnamed and unknown to him. He couldn't tell you the species or genus of the plants, the trees, or the flowers that bloom outside his windows, or how best to care for them. But bloom they do, because in spite of his inattention they've managed to get what they need to survive. Sunlight. Soil. Water.

Which is not to say they couldn't do with a little help. Some pruning, some pollarding to clear the way for new growth.

If he brushed away the fallen, dried leaves that crunch in clusters along the walkway, it would be easier to reach his front door. If he tended to the weeds that threaten to choke the more delicate flowers, he could better see their blossoms. But he doesn't think to do it, and they live on in pretty, if precarious, complacence.

If he watered the roots of the tree that dominates the very center of his yard, it might bear fruit. But though its bark is brittle, its limbs are sturdy enough for anyone wishing to climb them.

Unsupervised, unmanaged and unchallenged, these growing things have become defiant, unruly. They thicken and thrive with a tenacity that their well-watched cousins in other yards needn't have.

Wild things live in my father's yard. He protects them, from a distance.

A duck has taken refuge against the west wall, under the spare bedroom window. She must feel safe, nearly shrouded from view behind fronds the size of dinner plates. Her white face, red rimmed eyes, and green-black body are exotic, and they captivate me. But when I try to creep closer to examine her nest, to look for eggs and take pictures, I am scolded and shooed away. Just leave her be, my father says. She aint bothering anybody. The duck has a frantic look about her. She meets my intruding gaze head on, and I have the feeling that even one step closer would move her to aggression.

My father doesn't seem to mind the downy white feathers that litter the landscaping and stick to his doormat. In fact, I suspect he takes a certain pride in the fact that she chose his yard to make her home, of the dozens that line his quiet street. At night I can hear her plaintive cry, and I wonder what need she's communicating. My father, on the other side of the house, sleeps through her call.

When, months ago, a kingsnake took up temporary residence in the lanai, my father chose retreat over confrontation. Rather than try and run the snake off or have it professionally removed, he recused himself and declared the patio off limits until the snake was done with it. He'll go when he's ready. He got in there; he can get back out.

Around the yard is a tall wooden fence, long since sun-bleached of whatever rich brown color it once must have boasted. It's dry and splintered, and while the grooves in the grain draw my eye in, I know better than to run my fingers down them. Rusty nails and jagged knots poke from it in irregular intervals. The fence was there when he moved into this house years ago, and he never so much as weatherproofed it.

But it keeps his yard safe enough.

My father doesn't spend a lot of time in his yard, or, I imagine, thinking about it. Inside, his house is a testament to his own interests, carefully curated with the furniture, the curios, and the decorating touches it took him decades to collect and perfect. But the things that grow and bloom and drop and die beyond his immediate sight don't trouble him much. When I show him close-up pictures I've taken, showcasing the glorious pinks and reds and purples of the wild things that flourish, right under his nose, he nods dismissively. He's unimpressed.

The wild things will keep growing, anyway. They'll keep coming to his yard for shelter, shade, and safety. And he'll help them find it, in his way.

Reunion

When my mother died, I found among her things an inch-thick stack of neatly typed letters on high quality stationery, chronologically ordered and carefully bound. They were in excellent condition: freed from their envelopes, unbent, unsmudged, and seemingly untouched by time. They were from my father. They were dated from the years during which he'd worked as an engineer at a remote Alaskan radar station while she had worked for Pan American in New York.

I knew the bulk of my parent's courtship had been conducted via long distance, broken up only by occasional, exotic vacations afforded to them by his excellent salary and her travel benefits. For two, three weeks at a time, they'd meet up somewhere far across the globe: Hong Kong, Israel, the Canary Islands. I knew all the stories. I'd seen all the Super 8 footage.

What I didn't know was that these letters existed. When I found them, you could have knocked me over with a feather. Not only because it was impossible for me to reconcile the idea of my curmudgeonly, cynical, and darkly jaded father with the impassioned, earnest, and lovestruck thirty-something his words revealed. And not only because trying to imagine my parents - two people who spent twelve years fighting tooth and nail through the most bitterly acrimonious and drawn out divorce imaginable - as the young, smitten lovers emerging from these pages was mind-boggling. What caused me to leaf through these love letters in absolute shock was the fact that my mother had even kept them.

Every word my mother had uttered about her ex-husband for the last twenty years of her life had been laced with contempt. Likewise for him. It didn't make sense to me that she'd be sentimental about anything from their long defunct love affair.

I realized immediately that it wouldn't be right of me to read the letters in their entirety. Skimming the first two had been enough to give me an idea of their contents: the soulful outpourings of a man who'd found his life's mate. Partly out of curiosity to see how he'd react, and partly because I wanted to abdicate the responsibility of keeping them, I cautiously broached the subject of the letters to my dad. He was nearly as floored as I was. He asked me not to read them, and to send them to him. I did so, gladly. Something about them bothered me. They were fucking with my world view.

I'd barely recovered from the surprise of the letters when my dad sprung a shock of his own on me. He knew I was having my mother cremated a few days later, and he knew from comments I'd made that the idea of keeping an urn with her ashes made me exceptionally uncomfortable. It was macabre in the worst way to me: macabre and funny. The truth was, I didn't trust myself to treat my mother's remains, should I retain them, with the respect they deserved. I couldn't imagine placing some godawful metal vase, hermetically sealed to prevent spills for Christ's sake, on my mantle and not finding it simultaneously horrifying and hilarious.

My dad knew this, so he asked if he could have them, instead. "And not to do anything nefarious with," he quickly assured me. "I'd just like to keep them, if it's all the same to you."

Go fucking figure.

Rather than try and summon deductive powers I didn't nearly have at the ready (I was, after all, a mite consumed with handling my mother's death) in order to suss out his true motives, I shrugged, thought fuck it, and made arrangements to have my dead mother Fed-Exed to my living father.

And so it was, nearly three years later, when I was faced with the task of going through my second dead parent's things, that I came across my mother once again.

She was in my dad's office, on the top shelf of a mahogany bookcase filled with outdated computer manuals and the sort of tacky bric-a-brac I'd been chiding my father about collecting for years (perhaps in subconscious anticipation of this day?). She was in a predictably ugly brass urn, the fattest part of which was laser cut with thick black grooves.

I couldn't help but laugh. My father himself had been delivered just that day to the mortuary where he'd pre-paid (ever the planner!) for his own cremation. In a matter of a couple days, I was going to be in possession of the ashes of both my dead parents. Just me. All mine. No other family to divide them up with (because, disturbingly, that is apparently a thing people do). No one else to stake a cremains claim.

What a lucky girl I am, I thought wryly.

Well, try as I do to avoid being an utter cliche, there aren't a whole lot of options, when it comes to dealing with the ashes of your dead parents. As far as I can tell, there are three: keep, dispose, or disperse. The first was never an option; the second, a little too callous even for me. So I had no choice but to be a cliche. Christ, I thought. Well, it's Florida. At least there's an ocean a block away. Burial at sea it is!

By the way? Don't judge. You have no idea the sort of dry humor and emotionless pragmatism you're capable of until you're syringe feeding morphine into the mouth of your cancer-crippled dad. You discover versions of yourself you never knew existed. You have to.

I drove to the funeral home to pick up my dad's ashes a few days later. I didn't bother upgrading him to an urn. As far as I was concerned, he was on a short layover. So he came to me bound up in a clear plastic bag that was placed inside a thick, red cardboard box. The mortician supplied me with a certified letter declaring the box's contents, that I would need to show TSA if I wanted to travel with it. And if you think I wasn't tempted to bring the remains home just for the sick fun of messing with people at airport security, well, you don't know me at all. Likewise, if you think I didn't text one or two of my close friends a picture of the box strapped into the seatbelt of the passenger side of my rental car - again, pay closer attention.

I waited until the dead of night before I did one of the strangest and hardest things I've ever had to do.

I placed my mother's urn, my father's box, a small flashlight, and a pair of scissors on the front seat of the car and drove to the water. I stuck the flashlight and scissors in my jeans, carefully cradled both sets of ashes in my arms, and walked down a short pier to the Apollo Beach shoreline.

There were four or five widely-spaced, rickety wooden steps that led down to the water, and it was extremely dark. I don't think I've ever taken steps with as much care as I did those.

It was a clear night, and the moonlight reflected off the water in a way that felt suspiciously scripted. The warm breeze was in on the conspiracy, too. Everything aligned to make this heartbreaking moment as sensually powerful as possible. You will not forget this.

I took almost an hour to say goodbye to my mom and dad. I thought about them not just as parents to me, but as individuals with complex, rich inner lives the depths of which I could only guess at. I thought about what made them special to me, and what made life special to them. I thought about their accomplishments and failures, their quirks and charms. I mourned that as a family, we'd drifted apart, but I treasured the fact that at that moment, they were both there in my arms, together again. I thanked them for what they'd taught me, what they'd given me. I meditated on the ways I would continue to parent myself, in their absence - on what I would take away from each of them.

And finally, I let them go, one at a time, into the warm, shallow water that lapped the lowest stair. And it wasn't a cliche at all.

Flour Girl

If you want to see an extremely disconcerted dog, take a bag of his human-quality dog treats into the bathtub and eat handfuls of them while you cry. Chaucer wasn't sure whether to be more anxious about my tears or that fact that I was eating his fucking cookies. His head nearly exploded. And don't judge. Do not judge. Those things are delicious.

—-

Lately I've been taking some very large checks to the bank. I keep getting the same teller, a very polished and pretty young woman. She gets a look on her face that belies her curiosity is to why this sloppily-dressed woman in dire need of a manicure and root touch-up is plunking down such heavy coin. So far she's processed the transactions without comment, but yesterday afternoon she gave in.

"I don't mean to be nosy," she started, through the window. And then she trailed off, letting me volunteer helpfully, "My father died." It was at this point that the bullet proof glass suddenly thickened up another inch or so, preventing her from hearing me. She cocked her head and frowned. What's that?

"MY FATHER DIED," I announced, at about ten decibels louder than I'd intended. I could tell by the hush that fell over the crowd of paycheck-cashing weekend revelers that they really enjoyed that uplifting start to their weekend.

—-

My neighborhood is filled with familiar characters. Homeless persons, some mental, some just destitute. Shopkeepers and small restauranteurs that step out onto the sidewalk when business is slow. Street vendors selling melted popsicles and bags of fruit.

There's this one old man who sells water. He stands on corners and under awnings and hawks bottles for half a buck. I think he might be a little bit crazy. He'll call out, "Water, fifty cents!" and then mutter something vaguely ominous under his breath like, "You gotta drink water. In this heat? You'll get dehydrated, you'll see." or "The pipes. It's bad water, in those pipes. People don't know. They'll find out."

For some reason, I love this. His fear mongering sales angle delights me, I don't know why. Probably for the same reason I love doomsday and dystopic movies: I not-so-secretly want to watch the world crumble. Anyway, I kind of want to buy his water, stand nearby drinking it, and nod in agreement at his prognostications. But I'm afraid he'll tell me what's actually in those pipes, and I'll have to find Erin Brockovich.

---

Everything I own keeps breaking, and it's making me feel like a character in a Philip K. Dick novel. There is nothing more depressing than having a house full of expensive broken shit. In the past six months, the following things have crapped out on me, or gotten effed up in some way: My dSLR (in the shop now) My vacuum cleaner (which now emits sparks when I vacuum, adding an exciting element of danger to my housekeeping duties) My french press (which, haha, I knocked over with the vacuum cord and shattered) My electric tea kettle (since replaced) My lamp shades (Chaucer flung brown drool on them) My upright clothes steamer (just straight up stopped working) My floor lamp (the floor step-on switch came apart).

Today, the “unbreakable” container my five-pound bag of flour was in broke. Can you guess how long I let the mess sit on the floor before I finally cleaned it up?

a) 3 seconds

b) 3 minutes

c) 3 hours

d) I'm just going to wait for Chaucer to develop a taste for flour. I

If you guessed d), you get a human-grade-ingredient dog cookie.

Low Resistivity: A Weird Love Letter

In the cold, concrete-floored basement, there's a shop table covered with the guts of dissected medical devices. Clipped wires and dials. Metal rods and needle-sized levers. These are the trappings of an electrical engineer. This is my father's office.

I don't mess with any of it, not that I'd get in trouble if I did. My dad encourages curiosity. The only things I'm forbidden to touch are the bench vise and scalpel blades. "You'll lose a finger," he warns, though about which I'm not sure. He encourages curiosity and questions, which occasionally I produce. I rarely understand his answers, however. I am my father's daughter in many ways, but not in this way. He will explain concepts to me a hundred times and I will never get them. That's okay. I'll get a lot of things one day that he never will.

Still, I like to be in it - this space. There is a sense of relaxed gravity, and intelligence. I'm only eight years old, I don't yet appreciate the sort of mind required for engineering. But there's something magical in my dad's tinkering, that I know. He brings things to life, often with visible sparks of energy. It's dangerous and delicate work, and requires all his concentration. I have to play quietly, if I'm going to be down here.

Right now I'm playing with a stack of ferrite magnets. Cool and smooth to touch, they are the color of coal and the width of dimes. I pry two from the stack and set them down on the table a few inches apart. Slowly, very slowly, I move one toward the other. The second magnet scoots away, powerless to resist the opposing polarity. Then I flip one magnet and reverse the game, seeing how close I can get the disks before they snap together in attraction. The click they make when they combine is eternally satisfying, and a sound that will stay with me forever.

---

I heard it tonight, in my memory, as the heat ran from your body to mine, and things I never understood made sense for the length of a lightning bolt.

Magnetism is a fact of the world we can neither force nor resist. And conductivity is how easily things pass between you and I, because of how we choose to minimize the space and the obstacles. That's all I need to know, anyway.

On A Windy Day

On a windy day, on a late afternoon in February, here's what you can do: You can walk the three blocks from your apartment to the store, because you need things. You need a new mop head, because you've been ever so slightly fastidious about your floor lately. You need index cards, because you've started collecting vocabulary words again - because you've started reading again. Words like marmoreal, canebrake, gracile, loblolly. You need toothpaste.

You can walk that three block stretch briskly, without a coat or a purse to weigh you down. You can navigate the rush hour sidewalk with ease, twisting to squeeze past a crush of disembarking bus riders, weaving lightly through exhausted businessmen in suits, briefcases linked with invisible chains to their wrists. You can feel the late winter chill on your face, and thrust your fists deep into the pockets of your sweatshirt, which is zipped tight against your neck. The wind will lift your hair and your spirits, as it always does, and without looking down, you'll reach into your back pocket, feel for a tiny button on the side your phone, and press it once, twice. Yes. Louder.

You can reach the far side of the main street, where the sidewalk opens widely, and finally get clear of the crowd. You can then be seized by a feeling of such unexpected, unadulterated, and embarrassingly unjustified happiness that it feels as though someone has shoved you from one spot to the next, across several degrees of uncharted latitude, through some unseen continuum of emotion and consciousness, indifferent to where you'll land. You'll marvel at how different this instant feels from the one just before it. You'll swear you could turn around, there on the city street, and see a fast-fading ghost of yourself stepping forward, ready to assume the moment you're in possession of right now.

You'll want to laugh, but instead you'll just take a deep breath, drinking it in with concentration, and with greed.

You can become acutely aware of your senses, your comportment, your gait. Objects will suddenly shed the cloudy scrim behind which you viewed them just a minute ago and come to life, extra-dimensional. Colors will be obscenely vibrant. You'll stare at the people you pass, fascinated, mystified, vaguely aware that what you're feeling is unreal, a trick, a dream, but wishing everyone else would wake up, too. How can they be so calm in the face of it?

It. What is it? What is it?

It's the undeniable certainty that life is devastating - in its beauty, and in its misery. It's the belief that not only will everything be ok - it already is. It's the knowledge that we are so interconnected in our experience of that beauty and that pain, despite the billion-odd individual paths we're on, that we may as well just stop dead in our tracks, look at one another, and laugh. Or sigh. Or cry.

Everything in your sight will charm and delight you. Every last everyday detail: the way a pretty blonde has carefully tied the belt of her trenchcoat into an off-side bow; the self-conscious jerk with which a teenaged skateboarder shakes his hair from his face, poised and ready for the stoplight to release him; the oddly comforting familiarity of the taxi drivers' faces, queued as they are in their regular spot: Eastern European, and African, and African American. I don't know a single one of them. I feel as though I've known each of them for years.

You can have the thought come dancing into your brain, boastful and irrational as it always is, that you feel things more intensely than other people. You can feel your mind schism at the thought, half of it prickling with shame - What makes you think you're so special?, half of it quietly agreeing - Yes. Yes, you do.

You'll wonder for the hundredth time if something inside of you is broken, causing you to feel such exquisite, heart-stopping joy at the most mundane of triggers - or if instead something in you is enhanced. Amplified. And, as always when this happens, the wind will stir the leaves in your mind, exposing their opposite, darker sides: yes, but.

Yes, but, even if it's true, even if the wellspring of joy runs deeper in you, so too does the sorrow.

And you can think, for the hundredth time, about diluting both the joy and the sorrow. About saying, Yes, well, the thing is, doctor, the depression really is unbearable at times. Yes, I know this pill will dull the brighter side of things too. On balance, though, I think it would be best.

And you can say, Fuck balance. You can say, Fuck balance, I'll take them both. Because you can, because you've been doing it your whole adult life.

That's what you can do, on a windy day, on a late afternoon in February.

Anything, Just Anything

Ten years ago today a hospice nurse whose name I don't remember came to the spare bedroom in my father's house to tell me he had died. Or maybe not. Maybe she told my boyfriend first. Maybe she told him in the kitchen, keeping her voice low, so he could come break the news to me himself. Maybe he woke me up to tell me, gently stroking my leg until I opened my eyes and waited for him to find the words. Or maybe I was already awake, and bracing for it. Maybe I looked at him pleadingly, secretly hoping it was over.

I don't remember.

Ten years ago today I sat in that spare bedroom, hugging my knees to my chest, humming to myself to block out the sound of the body bag zipping shut, because my father had died ten feet from where I was still alive. Or maybe I didn't. Maybe I lingered in the doorway, morbidly fascinated by the whole scene, numb enough to watch the collapsible gurney get wheeled out into the Florida sunshine.

Maybe it was both. I don't remember.

Ten years ago today I texted Mason, whose own father had died a few years before, one single word: fin. His own one word reply came quickly: triste.

That I do remember. That definitely happened, just like that.

I don't remember much of what happened the day my dad died. I remember other things instead, like the incredible love my boyfriend and friends showed me, from the minute I found out he was sick until he was gone thirteen days later, rolling onward for months after I went back home to LA and dealt with the fallout. I am endlessly grateful to myself for writing it all down. If you go back to my posts from April 2012 to fall of that year, you'll see. You'll see how deeply I was loved, and how many magical moments I experienced in all of that love.

But back to my dad.

I remember things about my dad that I've never written down or talked to anyone about, because the only people who would nod and laugh, well, they're gone too. So it's just me left to remember the random, weird shit about my dad that pops up out of nowhere, like when I do laundry.

My dad was a laundry guy. Me, I'm not a laundry person. I will wear the same thing five times before I wash it, and even then I do so unwillingly, sure I am degrading the precious, expensive fibers of my favorite pieces. But my dad fucking loved doing laundry. He kept his washing machine and dryer in the garage, and kept them immaculate--just like the garage. And he did laundry all the goddamn time. Washed his clothes seemingly daily. Didn't care about shrinking them. And they were already pretty tight to begin with, because despite his best efforts towards staying fit, my father put on a few pounds every year. That can happen when you slam nom M&Ms during Soprano binge sessions.

And my dad's wardrobe stop evolving sometime around 1989, so we're talking corduroy short-shorts and polos in colors that haven't been fashionable since the Reagan administration. Lots of banana yellow. Oh, and no fabric softener. My dad was anti-fabric softener. Not an allergy issue. Possibly a cheapskate issue? I'm not sure. But there he was, with his stupid, shrunken polos keeping no secrets for his sixty-something belly, and the ridiculous shorts that crept alarmingly high when he sat down. He was an absolute clown in this regard and I would give anything, just anything to run the stupid fucking rough fabric of one of those stupid fucking canary yellow polo shirts between my fingers, because maybe it would help me remember whether I was even in the room when they took my father's body, because I should have been.

I should have been.

Ten years is a long time. You get a lot of scar tissue built up in ten years. But life is ever armed with a scalpel, and it can cut you back open in an instant, and nothing you can do about it.

If the only day I could have with him again was the day he died, I would take it. I wouldn't have left the room, selfishly, childishly, to go nurse my own heartbreak. I would have stayed by his side and not averted my gaze once, even though his own eyes were glazed over and elsewhere already. I would have kept telling him things that he wouldn't have heard, about what his love had meant to me, and all the ways his personality had shaped mine. And if I could go back to April 30, 2012 but take April 30, 2022 with me, I would lean close and whisper all my news. Dad, guess what? My company is sending me to a gala. They're sending me to big fancy black tie party because they believe in me, and think I can make good things happen.

And I would tell him that after the gala, I'm going to go spend the weekend with someone special in this new city I've made home. And Dad, get this, I would whisper. He's an engineer, just like you. But much better looking. And here I would pause, for laughter that wouldn't come. Then I'd continue:

And yes, Dad, sometimes I am sad like mom and sometimes I am lost like Matt. But I am doing the best I can out here for all of you, and I'm sorry you're not here to see it.

That's some of what I would say. And then I would be quiet and still and let him fall asleep, and I wouldn't leave for anything.

Dear Mike Deni

Ten years ago this past August, on the second Saturday of the month, I stood on a hill in Golden Gate Park with a plastic cup of wine in my hand. It was cheap red concession stand wine, and it was my second glass in an hour. I was trying to get drunk. I was trying to get drunk so I didn't feel so self-conscious about being at a music festival by myself. I wanted to join the crowd down below, where dozens of people were about to watch a set I had carefully chosen from a lineup of several possible choices. It was a group I'd never heard of until just a few months prior, but something about their music made me put them on my schedule. I wanted to join the growing group of fans, but I wasn't ready yet.

It was a cloudy-cool summer day, in a painful but also wonderfully memorable year. My dad had died a few months prior, and I'd been in a state of semi-mania ever since. Parties and bars, dancing and drugs, nonstop nights out with friends. All the while a three-inch thick binder of paperwork shoved to the back of my kitchen cabinet, haunting every minute of my fun: my dad's will, estate papers, and everything I needed to do to get his affairs settled and my inheritance safely administered. I was simultaneously terrified of it and thrilled by it. I knew it meant financial security and a fresh start for me. All I had to do was pull myself together and get a job, any job, and I would be okay. The depression and anxiety of being shiftless, of having no direction--none of that mattered now. I would be okay, if I could just face down the panic-inducing task of sorting all the legalities out and taking my first, belated steps towards real independence.

The binder sat and waited. It waited for me to catch my breath after his death. To fly home to LA from Florida and accept reality: Mom and Dad both gone now. On my own for real this time. The binder sat and waited while my friends swooped in with love and laughter to be a short term surrogate family. The binder waited while my boyfriend took me to Bonnaroo. And the binder was there listening when we broke up soon afterward, the terrible weight of my grief flattening us beyond repair. The binder knew it was a bad idea to go to Outside Lands, but we'd already bought the tickets. We figured we could travel separately, maybe meet up for a few hours as friends, catch a little music together.

Cut to day two of the festival. There I was with my wine, my mixed feelings of loss and gain, and all the insecurities that were keeping me from walking down the hill to be less alone than I needed to be. I felt, somehow, both broken and invincible. A difficult past, a family full of trauma and conflict, all the arguments and unresolved anger between my father and I--it was finally gone, gone, gone. No one to frown with silent disappointment at my mistakes anymore. No one to offer criticism but never help. My every choice going forward would be weightless, free from judgment. I could do and be whatever I wanted...if I could only figure out what that was. And in the meantime, music.

The band started up. My heart began pounding, hearing that unmistakable synth-pop sound. Taking the microphone from its stand, you addressed the crowd. And something about what you said or maybe just how you said it--it was like a key turning in a lock. There was a gentleness to it. A humbleness. A recognition of the gravity of the moment. Yours wasn't the biggest band on the lineup, and didn't command the biggest crowd. It was just exactly what I needed, to feel safe enough to lose myself in sound and celebration, to remember what could be beautiful so I could start to forget what had been ugly.

"Alright, you guys ready?" A tremor of excitement as bodies started to move. "Let's do this."

That's all you said. But it was the invitation I couldn't resist. I tossed back the rest of my wine and took deep, quick steps down the hill to come listen to you, alone but not.

---

No one ever warns us to keep some music to ourselves. So we share it, to amplify its meaning. To get even higher on it with another than we can get when we are alone. We draw a triangle between ourselves, the one we love, and the song that we've come to believe belongs to us both. With great consideration and ceremony, we place a piece of our heart inside that triangle. We need to. And it's every bit as intoxicating as we knew it would be.

What they don't tell us is that we'll never get that piece of our heart back. Forever after, the association is galvanized. Good luck separating those songs from the ghosts that cling to them. It's impossible.

But I never shared your music with anyone. It's mine alone. After the festival, I revisited your songs again and again over the years. But I never played Geographer for anyone. It became a signifier of a kind of solo inner life that began that shimmering summer ten years ago. Every time I hear Verona, I can reconstruct the moment exactly. The slight chill on my underdressed arms. Hellman Hollow filling up with day two attendees. Laughter and chatter and music everywhere. My indecision about whether to plant myself on the hill and watch from a distance, or get lost in the mix of welcoming strangers. Then you spoke, and my decision was made. And ever since, the sound of your voice reminds me of my independence and strength. Of my ability to crawl through difficult days, to face down binders and breakups, to break down and bounce back without anyone else's help. Your songs are my selfish, secret strength.

People worry about me on Thanksgiving, but they do so for the wrong reasons. They worry because I am alone, but really they should worry because I am not. The table is set for one but there are uninvited guests everywhere. My parents are here. My brother, too. They all want me to remember the simple happiness of sitting down to a meal surrounded by the ones that mean you must be home, safe. I don't want to remember that. It's too wonderful and it's too far gone.

On a day when there is always so much to be thankful for, today I am thankful for you. To my left and to my right, memories surge that threaten to pull me down into a deadly well of sadness. But your voice is a through line, a bright, beautiful wire on a cloudy day--again. Ten years I've been listening, without realizing until now just how much it means to me.

So thank you.

Music and Death

Last night I met up with a friend who I haven't seen in months. We had a great talk. Or rather, I talked, at great length, and he obligingly listened while I was variously self-indulgent, mopey, maudlin, macabre, and morose. What was I talking about, that would merit such descriptors? Music and death. I've come to be quite the expert on those.

I told him that this year, I've become more emotionally invested in music than I ever was before. I always had been, honestly, but now it feels almost alarming—the ease with which certain songs can bring me to my knees. Take the Of Monsters and Men album, My Head Is An Animal. No really, pack it up and take it away from me, because it demolishes me to listen to it. I can barely stand it. But it's a beautiful sort of demolition. I'm broken down and rebuilt every three or so minutes.

Catharsis doesn't even begin to cover what I feel, listening to those songs. They wrote my life. Those warble-voiced Icelanders just sat down and wrote my life. There's love, loss, grief, pain, hope, comfort, and family to be found in the lyrics. I dare anyone who's struggled to love or be loved by a parent to listen to Sloom. I defy anyone who's fought with depression to not connect with Little Talks.

I discovered My Head Is An Animal around the time my dad died, and it carried me from those black days through the grey ones of losing A. It will forever be a lifeline to a time of pain and growth, and I'm grateful for it. But I'm also unnerved by how easily those harmonies can upend me.

Anyway, that's what I said to my friend about music. Having primed him with this cheerfulness, I proceeded to further lighten the mood with an anecdote about my mother's death.

When my mother died, my husband helped me clean out her apartment. There was next to nothing of value in her belongings, but her pantry was full to overflowing with perfectly serviceable dry goods and non-perishable food. My husband discouraged me from taking any of it, but I did anyway. I don't know what made him uncomfortable about it. I guess just the fact that she was dead? Maybe he found it macabre, to touch the things of a dead person? As if her cold, clammy ghost hands had left cold, clammy ghost fingerprints on the plastic wrap of the paper towels.

Anyway, I took two grocery bags' worth of stuff. Mostly canned food. The sort of crap that probably killed her: Chef Boyardee, deviled ham, salt-laden vegetables. I brought it home and put it into our cabinets along with our own food. My husband wouldn't touch any of it, and neither would I, at first. For months, it lurked in the back of our cabinets, passed over but not forgotten, while newer, fresher, and healthier foodstuffs came and went around it.

Then one day, I opened a can of her chicken and rice soup, and heated it up on the stove.

I ate it slowly, thoughtfully, deliberately. I tortured myself with it. I wondered how each spoonful would taste to her. Salty? Too hot, perhaps? I remembered how she looked when she blew on food to cool it, and I pursed my lips in the same way. When the bowl was empty, I felt sick. Remorseful. Like I'd taken something of hers - something extremely personal - and used it, without permission. Like I was using her. Using her up.

It was a game of self-flagellation that I drew out for the next several months. Something would trigger a memory, and I'd suddenly feel overcome with longing for my mother's arms. But there was nothing I could do. The closest I could get to her was this shitty canned food I'd pillaged from her kitchen. So I'd eat some of it. And again: guilt. I was trying to fill myself up with her, but with each bite gone, there was a little less of her left.

Eventually, all that remained was some plain chicken broth. I took an hour to finish it. Swallow after swallow of cold, oily water. I wanted to cry, eating it, but I couldn't. I didn't feel anything. I wasn't even hungry. I wanted to be close to her, but maybe I wanted to hurry up and get the awful exercise over with, too. I needed to feel her inside me. I needed to get her out of my system.

More than once this summer I've had the full, conscious thought, Thank god I only had two parents. I couldn't do this again. You fight with them. You fight to love them, to understand them, to be understood and loved by them. You struggle to relate to them, to identify with them. You reach an age and a maturity where you finally start to do that, but now you're also old enough to fully appreciate the damages they did to do. You forgive them, or you don't. You secretly wish them dead, or you hope they'll live forever.

Then one day they're gone and no matter how complicated your relationship with them was, you miss them so much you could throw up, even though there's nothing, nothing, nothing in your stomach.

Miles Yet Left

I didn’t find out until fall of 2016 that my brother had died that summer.

I only had one brother. He was four years older than me. He was an addict, a violent criminal, and mentally ill. When he died I hadn't seen him in nearly a decade. The last I spoke with him was when our mother died; when our dad died we had no contact whatsoever. His final parole officer was legally obligated to send me warnings that he still made threats on my life. He didn't recommend reconnecting.

Anyway, regardless of all this, learning he'd died (of liver poisoning) knocked the wind out of me. In fact that's very much what it felt like--like a deflation. Like a sigh. Like a third tire going flat on the saddest, most beat-up station wagon ever to limp along the road. In this tragicomic metaphor, my family is of course the station wagon. A car full of alcoholics, anger junkies, depressives, and well-intentioned failures. I'm allowed to say this, being one of them.

When that third tire went kaput, it was like Well fuck. Now what. You motherfuckers all skipped town, and now I'm the only one left, to what? Elevate the family name back up to some baseline of respectability? Prove that our existence was worth something? Well, you guys upvoted the wrong one. Prepare for an afterlife of disappointment.

I've had a lot of cheese-stands-alone moments in my life, and this was the loneliest cheese I'd ever felt myself to be.

And when I got over myself, I mourned for him, and all the happinesses he might have had. Did have, a very long time ago. I cried for the little boy who pulled his littler sister in a red wagon down a sidewalk in a town so small it didn't matter if they got lost. A smart if difficult boy who loved paper planes, then model planes. A boy who hid from the things that troubled him in boxes of baseball cards, then British Invasion box sets. A teenager whose fucked-up internal wiring was all too easily ignited by some fucked-up parenting. My brother didn't stand much of a chance, to be fair. Our parents were a mess. Our household was a mess. I survived, relatively unscathed, by the skin of my teeth.

So yes, there it is I guess. This post ostensibly about him is really about me, and how I moved on from the death of my last remaining immediate family member: easily enough. Like a patched-up tire with some miles yet left on it. Like you do.

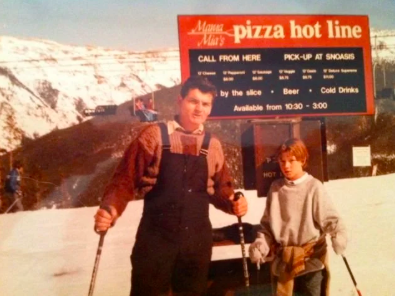

call from here

Alex: Thank you for calling Mama Mia's Pizza, Alex speaking. What can I get for you today?

Me: Hi, Alex. Um, I was wondering if you guys deliver?

Alex: If we deliver?

Me: Yeah. Do you offer delivery?

Alex: You mean...like, to the mountain or something?

Me: Well, no. I was actually hoping you could send it a little further than that.

Alex: (pause) Where exactly would you like your pizza delivered, ma'am?

Me: Los Angeles.

Alex: Los Angeles?

Me: That's right.

Alex: You want me to deliver your pizza to Los Angeles.

Me: Yes, please. But there's one other thing. I need you to deliver it to future, too. 2013, to be exact.

Alex: (sigh) Look, lady, we're really busy here, so thanks for the prank call, but--

Me: Wait! Don't hang up! Please don't hang up. I want something. I want to place an order. I'm just not sure I can get back to you. I'm having a hard time remembering, that's all.

Alex: Okaaaay, wellllll, did you want cheese, pepperoni, sausage, veggie, or supreme?

Me: Ummm, I think he'd want sausage. Or maybe supreme. Yeah. Supreme for sure. Except no mushrooms. He hated mushrooms.

Alex: So this is for two people?

Me: Yeah. Just two. I think. Well, I don't know. I don't remember who took the picture. It could have been my mom, or it could have been a stranger. But I think we might have gone alone...

Alex: Ma'am...?

Me: Sorry, yes, just two. So a medium I guess?

Alex: Ok, medium supreme, hold the mushrooms. That'll be eleven dollars, ready in twenty minutes, and you can pick it up at Snoas--

Me: Alex?

Alex: Ma'am?

Me: Could you just...could you just tell me what it's like there today? You know, like, describe it a little bit? It's been a really long time.

Alex: What it's like...where, ma'am?

Me: There. Wherever you are. I'm trying, but I just... I can't...

Alex: Ma'am....? Are you...ok?

Me: Yeah. I'm good. It's just...it's a year ago today that he died, and I'm looking through all these photographs, and most of the moments I remember, but I don't know which trip this was, or what it was like, and I don't even care about the place or the date so much as I just...I just want to be there, yanno? In my mind, just for a few minutes. I want to close my eyes and feel what it was like. But it's been so long, almost thirty years, I don't even... I can't...

Alex: Ok, ok, calm down. One sec, my manager is yelling at me...

(muffled voices)

Alex: Alright look, I'm on my lunch break in a few minutes, anyway. What it is you want to know?

Me: Just tell me about the place where you are. About what it's like there today. Anything at all.

Alex: Okaaaay, well, I'm in a shack the size of my parent's bathroom at the bottom of a big ass mountain. It's not snowing today, but it did last night, so the powder's pretty good, and everyone's in a good mood. They're tipping for once, anyway. Some little girl left a sweater in here a little while ago, so I gotta--

Me: Wait, what did you say?

Alex: Some little girl. She was in here with her dad. Cute kid, total tomboy. Looked exhausted though. They got a supreme pizza and sat at the counter. The kid picked all of the veggies and stuff off of it and put them on her dad's slices. (laughs) Anyway, yeah, she left her sweater, or I guess her dad's sweater, it's pretty big. I gotta run it over to lost and f--

Me: Alex?

Alex: Yeah?

Me: Listen, I'm sorry to be a pain in the ass, but I need to cancel the order. I can't...I can't get to you. I'm sorry. I wish more than anything I could, but I can't.

Alex: So no medium supreme?

Me: Yeah. I mean no. Not today. But thank you. Really...thanks.

Alex: Sure, no problem, I didn't put the order in yet, anyway. Have a good day, ok?

(dial tone)